Caregivers can often feel guilty when taking care of a terminally ill family member. Am I doing enough? Did I make the right decision? What if… what if…? Here are ways to recognize your feelings, tips for accepting them, and ways to forgive yourself.

Caregivers can often feel guilty when taking care of a terminally ill family member. Am I doing enough? Did I make the right decision? What if… what if…? Here are ways to recognize your feelings, tips for accepting them, and ways to forgive yourself.

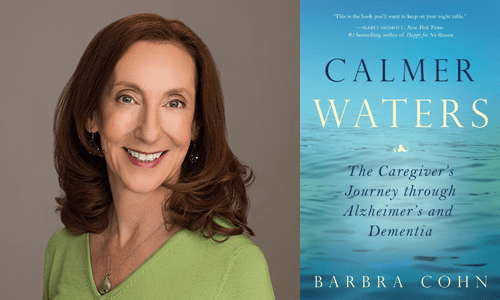

For dozens of tools and techniques to help caregivers feel happier, healthier, more confident, deal with feelings of guilt and find inner peace read “Calmer Waters: The Caregiver’s Journey Through Alzheimer’s and Dementia”

Some philosophers and psychologists believe guilt is mental and emotional anguish that is culturally imposed on us. Tibetans and Native Americans don’t even have a word for guilt, which might mean that it isn’t a basic human emotion. Yet, Jews and Christians are very adept at feeling guilty over trivial mistakes, as well as serious blunders.

The first time I felt guilt was when my brother was born. I’m two years older than he, and in 1954 the hospital rules didn’t allow siblings to visit newborns. My Uncle Irv placed me on his shoulders so I could see my mother, who waved to me from the window of her hospital room. I was angry with her for leaving me and I refused to look at her. She waved like the beautiful lady in the fancy red car that passed me by in the Memorial Day parade. But I wouldn’t look at her. The memory is a black and white movie that has replayed itself throughout my life, with the film always breaking at the point when I sullenly turn my head away.

For years afterwards, I would awaken in the night feeling guilty that I didn’t look at her. When I was four years old, I fell out of bed onto the wooden floor of the bedroom I shared with my brother because I was having a bad dream. I don’t recall the dream, but I remember the ache inside my chest that has always been associated with not doing what my mother wanted me, or expected me, to do.

Over the years, up until my early fifties, I’d have a physical sensation that felt like sand paper or grains of sand inside the skin of my hands that would migrate to the skin and muscles of my arms and torso. Sometimes it felt like my arms and hands were paralyzed or had grown in size. It was hard to move, and the uneasiness of guilt was always associated with the sensation. I recently realized that I haven’t felt those sensations in a very long time.

Maybe I lost those sensations because the guilt of my childhood was replaced by the guilt I felt over placing my husband in a memory care home. I could have taken care of him until the end of his life, but I was drowning in misery and I promised myself I wouldn’t sacrifice everything for this illness. I prayed for his release and my relief, and knew that if I had taken care of him until the end, my own health would have suffered.

I tried to help my husband fight Alzheimer’s by bringing him to healers, holy people, and complementary medicine practitioners. I fed him an organic, whole-foods diet and gave him nutritional supplements, in addition to the prescribed pharmaceutical drugs. I ordered Memantine from Europe before it was FDA approved and prescribed as part of the Alzheimer’s drug protocol by U.S. physicians.

I did all this until I finally realized that my husband needed to take the solitary journey of being a victim of Alzheimer’s disease. Some call it fate and others call it karma. Whatever we name it, no matter how much we are loved and in close communion with family and friends, we have to travel the delicate path of life on our own. When we succumb to illness and disease, it becomes especially painful for others to helplessly stand by and watch, after doing everything humanly possible to assist.

There was always one more “magic bullet” for my husband Morris to try, and yet when I felt the possibility of divine intervention weaken, I began to give up hope and let destiny take its course. The first couple of years after Morris’s passing, the guilt—and grief—would unexpectedly grab me, wrapping its tentacles around my chest. It would twist the insides of my stomach, making it impossible to eat. It would swell into a lump in my throat or tighten a band around my head, destroying my serenity for an hour or two —or an entire day.

Guilt came in layers, piled up like the blankets I tossed from my bed one by one during a cold winter’s night. The blankets came off as my temperature rose and drops of sweat pooled between my breasts. I shook off the feelings of guilt in a similar way when I heard my therapist’s words in the back of my mind reminding me that I did more than I could do; when I remembered that I’m a mere mortal who breaks and cries when I can’t move one more inch beyond the confines of this physical body; when my heart had expanded to the point where it can’t expand anymore, so it has to contract in order to plow through the walls of pain and deal with the guilt.

Why do I still feel guilt? I feel guilt about not being the perfect wife before Morris got sick. This man adored me and I didn’t reciprocate with a passion that matched his. I feel guilt because I’m alive and he’s not. (Survivor’s guilt is commonly felt by those who share in a tragic event in which the cherished partner dies, leaving the other one to live and put back the pieces of the life they once shared.) I feel guilt about the times I could have spent with Morris watching television or taking a walk instead of running out to be with friends or to dance. Feeling guilt for doing anything to get away from his asking me the same question over and over again, or so I wouldn’t have to watch the man who once stood tall and proud, stoop and stumble like a man way beyond his years.

I hear the therapist’s voice in my head asking, “What would you say to someone who just told you all this?” I’d say, “But you did the absolute best that you could do.” And then I feel better. It’s okay. I’m okay. I really did the best I knew how, and Morris lived longer than his prognosis because of it.

Now, almost eight years after his passing, the guilt appears much less frequently. It hovers momentarily like a hummingbird poking its beak into honeysuckle and hollyhock. The guilt is diluted and flavorless like cream that’s been frozen without added fruit or chocolate chips. It’s a color without pigment, a touch without pressure, a sound without notes. The guilt I feel now is background noise; not noticed until I turn off the other sounds in my world or mindlessly drive my car on a dark, damp day, which is unusual in sunny Colorado. The guilt now appears in various shades of dirty white and brown. It doesn’t reach inside my heart with its claw like it used to. The battle is over, and almost, but not quite, won.

Why do you feel guilty?

- Do you feel that you aren’t doing enough for your care recipient? Make a list of everything you do for the person you care for. Preparing a meal, shopping for groceries, driving to appointments, making a bed, doing laundry, making a phone call, sitting next to the person, even just giving a hug: the list adds up! You are doing a lot more than you think you are!

- Are you guilty about your negative feelings? Resentment, anger, grief are all normal. They are just feelings and they aren’t wrong. Feelings are complicated and you are entitled to them. You probably love the person you are caring for but the time you spend is precious and you might rather be outside gardening or hiking or traveling.

- Do you feel badly about taking time for yourself? Don’t! If you don’t stay well, including eating and sleeping well, there’s a good chance you will get sick. And that is not going to help anyone! Please take some time for yourself. If you are a full-time caregiver, at least take a 15 minute walk every day. Get some respite care. Your local county social services department can most likely provide you with some options for help.

- Are you feeling inadequate at a caregiver? The Alzheimer’s Association offers free classes on caregiving. “The Savvy Caregiver” is an excellent five-session class for family caregivers. It helps caregivers better understand the changes their loved ones are experience, and how to best provide individualized care for their loved ones throughout the progression of Alzheimer’s or dementia.

Tips for easing guilt

- Ask yourself what is bothering you. Talk with a close friend who will not judge you, or with a professional therapist, clergy person, spiritual teacher, or intuitive guide. Talk about your guilt until you feel your body release the tension that is stored in your muscles and cells.

- Remember that you are human and not perfect. No one expects you to perform with absolute clarity and grace all the time.

- You cannot control everything all the time. You are doing the best that you can with the information, strength, and inner resources that you have.

- Have an “empty chair” dialogue by speaking out loud and pretending that your care partner is in the chair next to you. Express your feelings openly and wholeheartedly. Ask for forgiveness if you feel that you wronged your loved one in any way.

- Write down your thoughts and feelings. Journaling is a wonderful, inexpensive way to release your concerns and worries on paper. It’s available when your therapist and best friend are not, and you can do it anywhere at your leisure.

- Strong feelings of guilt, remorse, and grief will diminish over time. If they continue to haunt you, seek professional help.